Then there was this review excerpt below the title:

“Not just the best novel I read this year, but the best mystery of the decade....” That’s high praise, I thought in a Nicholas Cage voice. And contrary to the title and cover art, it’s a mystery; I found that interesting. Oh, that review excerpt was by Stephen King. THAT’S HIGH PRAISE, I screamed in my head in my own voice. I was sold even before Stephen King’s pitch. This was during a time in my life where little marketing attributes, like a title or cover that seems slightly out of place, were enough to make me buy a book. This was also a time when I was adamant about finishing any book I started, no matter how awful. Luckily, I wasn’t in such a bind. Case Histories by Kate Atkinson is great. What wonderful powers of deduction you have Mr. Brodie,” Julia said, and it was hard to tell whether she was being ironic or trying to flatter him. She had one of those husky voices that sounded as if she were permanently coming down with a cold. Men seemed to find that sexy in a woman, which Jackson thought was odd because it made women sound less like women and more like men. Maybe it was a gay thing.

The Jackson here is Jackson Brodie, a former cop and now private-eye. He’s a melancholy small-time P.I. who pursues small-time ineffectual cases like infidelity accusations. This changes when three seemingly unrelated cases find their way to him. One is the case of Theo Wyre.

Theo is a lawyer who, as exhibit by the quote above, dotes on and greatly loves his daughter, Laura. His over-protection of her is what leads to her untimely death though, when she is stabbed in her father’s law office, the killer going unfound.

Time did not heal – it merely rubbed at the wound, slowly and relentlessly. The world had moved on and forgotten and there was only Theo left to keep Laura’s flame alive. Jennifer lived in Canada now and although they talked on the phone and e-mailed each other, they rarely talked about Laura. Jennifer had never liked the pain of remembering what had happened, but for Theo it was the pain that kept Laura alive in his memory. He was afraid that if it ever began to heal she would disappear.”

Theo’s become a sort of out of shape recluse since Laura’s passing. He seems to wallow daily in the sorrow of her loss, in a reserved, English sort of way (at least as his story is told to us.) This general reserve is useful in making passages which describe his love and loss all the more pointed.

Theo never doubted for a moment that when he died he would be reunited with Laura…. It wasn’t that Theo believed in religion, or a God, or an afterlife. He just knew it was impossible to feel this much love and for it to end."

As an American, I might dramatize the collective British psyche, so take the following perception with a grain of salt. Theo’s anguish over his dead child, his talking to God even though he doesn’t believe in one, his belief that the love he and his child shared couldn’t just evaporate with death – these are miniature aspects of a larger British sentiment. The UK is known for both a longstanding stiff-upper-lippery and a growing atheism. I speculate that during the last century science and war have exacerbated these characteristics. But the latter has also fomented a kind of unity that contains, to a certain arguable extent, intangible spiritual agreement. I wonder if the newest UK generations, not directly related to anyone who had to withstand a military attack, will possess the conditions I describe.

All this to say that Theo isn’t the only outwardly “reserved” character; all of the protagonists and suspects and instigators are. The plotting on a whole is held back, stripped of some common crime novel thrill formulas, and replaced with keen (sometimes witty) observation.

I think I’ve already Americanized a few words in this review. Dope!

As a pair, the Amelia and Julia quoted above are one of Brodie’s three clients. In childhood their younger sister, Olivia, went missing, never to be seen again. When their stodgy professor father dies and they find one of Olivia’s toys in his desk it peaks their suspicion – or longing for closure – and they hire Brodie to pursue the tragic cold case. Another of Brodie’s three cases involves Caroline, who murdered her husband in a fit of rage. The act itself and the time in prison for it drastically estrange her from her sister, Shirley, and her daughter, Tanya.

The dutiful love mentioned in this excerpt is also dwelt on by Brody, in relation to his own family.

Even with Brody’s deflection at the end there, the ideas of obligatory love in Case Histories struck me as a valuable and pertinent reminder. Across the [Western] world we seem to be getting quicker to abandon those who don’t benefit us, or have betrayed us, or are hard to get along with. Our self-comfort and anger increasingly take the helm over a sense of duty in relationships. I say “we” and “our” because I’m ever guiltier as I age.

Back to the Caroline and Shirley subplot. After Caroline’s sentence for murdering her husband, she makes a new life (changes her name to Caroline) and marries again. This husband is wealthy, comes with his own children and an annoying mother. Rowena, Jonathan’s mother, talked all the time about 'breeding' because she had a stable of hunters (big, frightening brutes), but sometimes she seemed to be applying the concept to her own family, and Caroline wanted to point out to her that natural selection led to a vigorous species whereas 'breeding' resulted in congenital defects, in pale, blond children who spoke French on Wednesdays and whose blank Midwich Cuckoo faces suggested latent idiocy. In Caroline’s professional opinion."

But Jonathan isn’t her only beau. She’s taken by a local priest.

Maybe he wasn’t the right person for her…. but surely there wasn’t just one person in the whole world who was meant for you? If there was then the odds against you ever bumping up against him would be overwhelming, and knowing Caroline’s luck even if she did bump against him she probably wouldn’t realize who he was. And what if the person who was destined for you was a shanty dweller in Mexico City or a political prisoner in Burma or one of the million people she was unlikely ever to have a relationship with? Like a prematurely balding Anglican vicar in a rural parish in North Yorkshire."

But while Caroline makes a new life, her sister, Shirley, searches the past. While Caroline was incarcerated, her daughter Tanya was left in Shirley’s care. Tanya eventually is made a ward of her grandparents, on her dead father’s side. They force what becomes and end to Tanya and her Aunt Shirley’s relationship.

Shirley hires Jackson Brody to trace the whereabouts of Tanya, who would now be a young adult. It is Brody’s narrative that interested me the most, maybe because I’m a simple sucker for the more sluethed aspects of a detective novel, and maybe it’s because Brody and his thoughts are just well crafted. Check these witty descriptions of him taking likings to women: Both Sharon and the Dental Nurse had dark, enigmatic eyes, and they had a way of looking at him indifferently over their masks as if they were contemplating what they might do to him next, like sadistic belly dancers with surgical instruments."

Brodie’s weathered, sarcastic, can handle himself, is divorced and rough around the edges, haunted by the murder of his own sister as he investigated the murder of someone else’s. Case Histories is really a miserable set of circumstances all around. His wit and his tagalong daughter provide some needed sunshine throughout.

Marlee began to grumble in earnest. “I’m hungry, Daddy. Daddy.”

Case Histories isn’t a nail-biter. Its heavy, the air and plot more something to chew on slowly than flip through. It isn’t even slow in a Law & Order procedural type of way; it’s a set of family dramas that unfold like crumpled paper into a complex mystery. Read it if you like meticulously reading great writing.

Buy Case Histories HERE

He had a great and devastating sense of humor that illuminated dark corners and prevented him getting a senior position.”

Published and set in 1962, Len Deighton’s debut novel follows an unnamed British intelligence officer as he tries to thwart the efforts of his meddlesome Soviet counterpart. Within the genre Deighton’s works are purportedly thinking-men's, more realistic, alternatives to Bond novels. I indirectly wondered a few paragraphs ago if that distinction wasn’t more earned by John le Carré. But as I mentally work through this contest, the realist aspects of spy fiction might actually, or at least seemingly, be championed by Deighton. Le Carré’s writing is melancholy and overtly deep-thought provoking, literary. Literary is a vague description but most avid readers will understand what I’m trying to say – Le Carré’s novels, even when narrated in first person, are narrated in artful prose. Because of this, Le Carré’s storytelling may come across as markedly more adorned than what one might expect of hard-boiled spies. I say may come across because Le Carré himself was a spy in MI5 and MI6, which incontrovertibly means that at least one real spy thinks the way Le Carré writes.

Deighton’s less flowery exposition perhaps just gives off a convincing illusion of realism. The IPCRESS File contains several matter-of-fact descriptions of spy craft including: Jean was doing a thing that men agents have to learn, but most women do naturally. She stood back and let the conversation move between the others, listening or guiding as needed.” ‘ 'When the end is lawful the means are also lawful,' I answered." ‘A spy has no friends’ people say; but it’s more complex than that. A spy has to have friends, in fact many sets of friends. Friends he’s made by doing things and by not doing other things. Every agent has his own ‘old boy network’ and like every other ‘old boy network’ it cuts across frontiers, jobs and every other loyalty – it’s a sort of spy’s insurance policy. One has no specific arrangement with anyone, no code other than a mutual sensitivity to euphemisms.” ‘You may as well go in,’ said a tall, bespectacled city gent behind us, opening the door with a key. We went in, partly because it was convenient for us, partly because there were two more city gents behind us, and partly because they were all holding small 9mm Italian Mod 34 Beretta automatic pistols.”

I’m really nit-picking the differences between Deighton and Le Carré. One could find similar types of spy-writing in Le Carré’s many novels too. They’re contemporaries. The last of the four quotes above does highlight a certain humor unique to Deighton though. Yes, there is levity in Le Carré’s work at times, but it often takes more searching for. Deighton’s unnamed protagonist and other characters are quick to irony and sarcasm.

My mother’s eldest sister wished I was in Geneva; so did I, except that my aunt was there.” Ross was a regular officer; that is to say he didn’t drink gin after 7.30 P.M. or hit ladies without first removing his hat” He wore a handful of Gold Rings, a gold watch strap and a smile full of jacket crowns. It was an indigestible smile – he was never able to swallow it.” Do you know, in Afghanistan a camel costs more than a wife? This old guy was sitting riding on his camel…. ‘Why aren’t you giving your wife a lift, Chas?’ I said. (We all called him Chas.) ‘No, there are minefields here near the aerodrome,’ he said. ‘You let her walk then?’ So he said, ‘Yes, it’s a very valuable camel.’”

The unnamed lead also provides spurts of comic relief with classic British self-awareness.

Ross and I had come to an arrangement of some years’ standing – we had decided to hate each other. Being English, this vitriolic relationship manifested itself in oriental politeness.” I was sufficiently English to find it difficult to say nice things to people I really liked, and I really liked Barney.”

The IPCRESS File and its sequels are lauded by many fans as a truer-to-life-than-Bond series. From what I could find, it looks likely that this sentiment was ascribed to the books after the adapted films were overtly contrasted against Bond movies in preproduction and marketing. Ian Fleming’s Bond novels and their cinema outings are certainly more adventurous than Deighton’s tales. But again, as was John le Carré, Fleming himself was a spy, so an awful lot of credit for realism has been given to the non-former-spy author Deighton perhaps simply for the novel’s slow pacing, which may only increase the seeming realism. I’m not sure.

“Slow” isn’t a pejorative here. Good spy novels can require diligent reading (see Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.) My judgment of a slow-paced narrative is only relative anyway. The IPCRESS File moves along at exactly the speed it should. And that’s not to say that “IPCRESS” shakes all the Bond tropes, thank goodness. There’s no prototypical gadgets or dare-devilish stunts, but there are bombs, hostage situations, gourmet meals, exotic international locations, high stakes, and bedded female supporting characters. The iced Israeli melon was sweet, tender and cold like the blonde waitress.” Its smooth light-brown top had the sensual color of the beach at Nice, when it is covered with girls, you understand.” Dark-skinned young men with long black hair parade along the water’s edge in bikinis almost big enough to conceal a comb.” Jean had pancakes and a thimbleful of black coffee without mentioning calories, and went through the whole meal without lighting a cigarette. This showed virtue enough, she must have some vices.”

Americans are much too brutal while they are trying to make money, and much too sloppily sentimental and even gullible after they make it. Before: they think the world is crooked. After: they think it quaint.”

*Note: Some editions are titled with an all-capital “IPCRESS” and some are titled “Ipcress.” It is an acronym in the book, so the earlier seems more apt.

Such wonderful writing populates all of Shades of Grey from front to back. The novel’s teen protagonist, Eddie Russett, settles himself into relegation in a new town within Chromatacia. This is the name of the book’s post-apocalyptic society, where class placement is based on the colors one can see. Rules and hierarchy come from the tenets of Munsell, the society’s founder. In our present world Munsell was an artist and inventor of a color system. The novel’s Munsell may not be so different from his real namesake. The difference is marked by Chromatacian’s interpretation of Munsell’s work. It makes for a fresh, thinly veiled allegory of Christian legalism and maddening idealistic bureaucracy.

[Rule #] 9.3.88.32.025: The cucumber and the tomato are both fruit; the avocado is a nut. To assist with the dietary requirements of vegetarians, on the first Tuesday of the month a chicken is officially a vegetable.”

The humor of Fforde’s first installment in an as yet un-continued series is cued naturally by great forbears like Alice in Wonderland, The Phantom Tollbooth, and A Series of Unfortunate Events.

....If you enjoyed laughing in the face of death, you might like to have a crack at High Saffron. One hundred merits, and all you have to do is take a look.”

Progressive Leapbacks had stripped so much knowledge from the Collective that we were now not only ignorant, but had no idea how ignorant. The moving stars in the night sky were only one small part of a greater understanding that had gone for good. And as I stood there frowning to myself, I had a sense that everything about the collective was utterly and completely wrong. We should be dedicating our lives to gaining knowledge, not to losing it.”

Chromatacia’s rigid hierarchy and myriad regulations leave a void that Eddie Russett feels a need to fill. Independent thinking is discouraged by the rules, but just as significantly (maybe more significantly,) genuine emotion has been washed out as well.

Those that can be troubled to muse upon the meaning of life are generally disappointed when they figure it out.”

The Apocryphal Men are alleged walking historical references, a seemingly invaluable resource to the uninformed general population. But Eddie Russett is young and discovering a passion that Chromatacia has been trying to erase. If the meaning of life is disappointing, as Mr. Baxter teaches, Eddie still wants to confirm it for himself. His longing for more, though shunned, is heavy and real. Other citizens even quietly sympathize with him.

“ Never underestimate the capacity for romance, no matter what the circumstance.”

SPOILER BELOW

“ Why didn’t you take the train? You’re almost certainly going to disappear off into the outfield tomorrow. And I know you can’t possibly want to marry Violet.”

END OF SPOILER

Cynics, like myself at times, may see that passage as young existential nonsense. But I believe Shades of Grey’s commendable point is whether existence or fate or a hybrid of both, human purpose and meaning are better examined and explored than dictated. That might seem like such a basic idea, but it’s especially important for young readers who feel stifled. And it may only seem basic because of how I conveyed it, but Jasper Fforde is a far better writer than I.

Note: Shades of Grey is also alternately titled, as part of the coming series, Shades of Grey: The Road To High Saffron

Lois Lowry’s magnum opus, The Giver, hit bookshelves in 1993. It was sometime in the mid-2000’s that I read it as part of my junior high school curriculum. I didn’t like every book they gave us but I did like The Giver, so much that for a while I was the annoying guy who gave the book to family and friends to read.

As a teenager I mistakenly assumed that anything in our English lit. syllabus was universally accepted as an important part of the literary canon. The Giver has been a critical point of contention since day one. It takes place in a future “Community” that has rebuilt from the ashes of catastrophe. The new order is cordial, serene, sterile, passionless. Community residents are given a utilitarian place in society – a career – when they come of age. The elderly are euthanized, but their deaths are called “releases to elsewhere” and there is no concept of life’s end other than the “release ceremony.” Family units are centrally planned but love is not discussed, practiced, or taught. There is no knowledge of anything outside of Community’s borders or from before Community’s formation. The way of things is not to be questioned. It seems strikingly similar to our Western perception of North Korea right now. Some critics believed The Giver to present an exaggerated, cherry-picked, hypothetical egalitarian dystopia, levying complaints similar to those of Ayn Rand’s Anthem. Some didn’t like that the science in the science fiction wasn’t well explained. Some simply thought it to be uninspired, too similar to previous staples like Nolan & Johnson’s Logan’s Run or Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury.

Guess what!? This isn’t even a review of the book though. This is a review of the film, which suffered through substantial development hell, taking twenty years to finally be made and released. (I’ll have to give the source a fresh read sometime and post a review for it.)

The Giver, directed by Phillip Noyce, elicited equally divisive reactions as the source novel. One added point of contention among viewers was the question of whether the film was true to its source. I’m in a slight minority that say it was, and the slight minority that say the film was great overall. Phillip Noyce is one of my favorite directors. His output is inconsistent (to me and viewers and critics) but his great films are some of the best ever. These are Rabbit-Proof Fence, Catch a Fire, and (I contend) The Giver. I’m in good company on my opinion of the last film. Author Lois Lowry said that she was so pleased with parts of her novel’s screen adaptation that it made her want to go back and change the book to be more like it.

During the months following his assignment, he trains under the outgoing Receiver, now the Giver (played by Jeff Bridges.) The Giver, memory by memory, transmits to Jonas the locked away aspects of a long lost world. One of these aspects is music.

Emotions and music are just two of many things that the architects and heads of Community have deemed too dangerous to be made known to the general population. The Receiver of Memories exists only to advise the Elders on how to keep problems of the past at bay.

“ Memories are not just about the past. They determine our future. You can change things; you can make things better.”

“We’d been told the Chief Elder knew everything, things nobody else did. But I had learned that knowing what something is, is not the same as knowing how something feels. I got lost, the good kind of lost. I saw sights and sounds I had no words to describe – faces with flesh of all different colors. I felt so alive. This was forbidden? I didn’t know what to think, what to believe. ‘Have faith,’ the Giver told me. He said faith – that was seeing beyond. He compared it to the wind, something felt but not seen. It was life; it just seemed more complete. The more I experienced, the more I wanted.”

Jonas and the Giver secretly forgo their daily injections. Every citizen is required to take them. They are purported to be a kind of multivitamin, but are really just emotional sedatives to help keep everyone docile. The Giver and Jonas abstaining from these injections heightens their perception of the memories they keep. They are made keen to the important kind of... soul that has faded from Community. This soul is difficult to clinically describe and in fact, shouldn't be taught clinically, at least not exclusively. A soul is fostered by experience, experiences that the Elders have relegated away to the archives in Jonas’ and Giver’s minds.

Jonas and the Giver plan to make a change, to release the memories of the past to everyone. But they must be secret and careful until the plan is in motion. The Giver had tried this once before, with a previous student, but it all went awry and she was “released to elsewhere.”

The Giver admonishes euthanasia, infanticide, eugenics, authoritarianism, emotional repression. These things lumped together into what’s presented as an oppressive egalitarian regime soured many viewer responses. Ideological naysayers viewed it as a subtle (or not so subtle) jab at several current societies. It’s a jab worth pondering. The film’s setting is governed by Elders who who euthanize babies that aren’t calculated to have viable prospects. Community is designed so that every home, building, and street has a utility, but no distinction. Citizens take daily injections so that (unbeknownst to them) their emotions never factor into decisions.

Circumstances in our world today are potential warning signs of our proclivity to move in the direction of Community. Work critically from the other side of that coin, and The Giver simply makes a point of what’s wrong with us now by scaling it up to a possible future. Iceland has recently been celebrated for eliminating down syndrome in their country, by aborting virtually every pregnancy with signs of it. Gated communities in places like Florida get fined by HOAs for having “unseemly” paint colors or grass that’s too high. Children and adults across the U.S. are increasingly prescribed sedatives like Xanax to temper anxiety, hyperactivity, depression, even slight social misalignment. Regarding the last example, I contend there’s an over-prescription. Multiple people who are close to me have undertaken a medicine regimen that masks their mental/emotional issues with docility. The bad stuff goes away but so does the great, and the problems aren’t so much solved as they are locked away along with personalities.

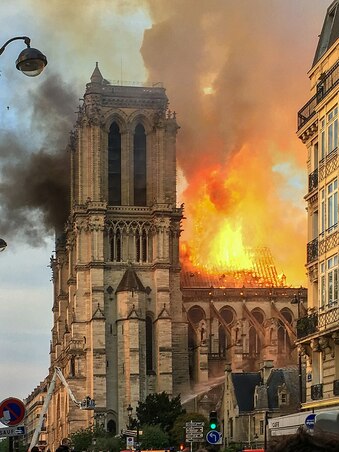

This week, Notre Dame Cathedral caught fire and burned for 15 hours. Despair was universal. Voices of support came from celebrities, politicians, every-day admirers, and even people who probably hadn’t given the cathedral a thought in years or ever. It wasn’t the most unsettling kind of catastrophe, because it wasn’t an act of aggression and no one was killed. But it did make a real-life point of the importance of things Community did away with in The Giver.

For the purpose of this review, I’ve so far been looking at the satirical motives of The Giver. I think it’s worth mentioning that it’s also a great character-driven narrative, and Philip Noyce brings that to the film version with a superb cast.

Lois Lowry asserts her aging father's memory loss inspired her to write The Giver. In her words, she originally “just wrote it as a story, as an exciting adventure…. It was only afterward that I realized out of that arises food for thought. A lot of questions were raised. I think the best books raise questions….” Give the book a read and the film a watch to both follow some compelling characters on an adventure and to consider the greater, ever-present, questions about what defines our humanity and what that definition is worth.

SPOILER BELOW

“ I wish I had been there when the memories returned. They were the truth. The Elders and their rules were the lie. So I do not apologize. I knew Fiona was safe, that I’d see her again, and that I held the future there in my arms. The Giver had led us here, to this house. It was real. From far behind me, from the place I had left, I thought I heard music too. Perhaps it was only and echo. But it was enough. It would lead us all home.”

END OF SPOILER

Also worth noting are the home video’s special features, which contain a wealth of BTS footage, interviews, a Comic Con panel, and an extended scene which in itself could be a great standalone short film.

The Dark Knight rises, but he is also the least significant of the main characters in The Dark Knight Rises, and that’s OK, sort of.

The most acclaimed comic book hero film series comes to an epic end as Gotham’s spirit and existence are tested by Bane, possibly with a little help from Catwoman. There’s so much good to be said about the third Nolan-directed Batman film. Anne Hathaway is a perfect Catwoman. Her sly remarks and femme fatale persona in no way come across as the product of expository stock characters or campy comic book goofiness. She’s sarcastic because she hates, not just because. Her distaste for the wealthy isn’t villainous, it’s more of a reflection of how many, especially people unfairly cheated by circumstances beyond their control, have felt during the on and off recession. Selina Kyle has to fight to survive and she’ll do whatever it takes, from being Bane’s hired hand to seducing congressmen to operating what might be an old-fashioned brothel, where Johns are actually marks who walk out with missing watches and wallets. She’s not relatively whorish though, especially in comparison to the last Catwoman we saw. Her cat-suit’s not from an S&M shop like in 2004 or even 1992. It’s practical this time; it’s a burglar’s work wear. It still manages to be tight and sexy over a toned Anne Hathaway, there are even some pinup photo opps when she straddles the Batcycle. Her swagger is never for the sheer sake of a pose though; her actions are always part of the big story. The big story was shot in the big city this time. It took me years to finally accept that Chicago would have to serve as the canvas for Nolan’s Gotham. The moment I accept it, “Rises” comes out and NYC not only serves as the backdrop for Gotham, but it’s pretty much made clear that Gotham is New York City. I’m glad Christopher Nolan figured that out, or maybe he just was offered an unbeatable production tax break – who cares? Gotham has been New York’s nick name for over a hundred years, so explicit exposition of city landmarks such as Wall Street, the New York Stock Exchange, The Queensboro Bridge, Sak’s, and a near-completed Freedom Tower were a nice surprise. It was somewhat unsettling, on a real-life level, to see actual city buildings and bridges crumble after goons walk into the NYSE and open fire on innocent nine-to-fivers. It’s a good kind of unsettling, at least for the sake of quality film, because the graver and more relatable a tragedy is, the more we need and yearn for the villain who caused it to be stopped.

The villain in question is Bane, a jacked up, intelligent mercenary set on destroying Gotham. His intended method is so extreme and harsh that he was exiled from the League of Shadows – that’s right, the same League responsible for Bruce Wayne’s training and the same League that almost destroyed Gotham in Batman Begins. Though he is intelligent, a point applauded and hammered into my head by even bigger Batman fans than me, his most effective threat to the Knight is physical. His mere presence is intimidating and grows as he proves to be many times stronger and many times a better fighter than Batman. He’s a worthy foe – a catastrophe that Batman had thought he ended with Ra’s al Gul, but only thwarted, providing intermission from the League of Shadows and time to deal with the Joker. Bane’s no Joker. His presence is heavy in every way and from the expression that we see on the half of a face that we do see, his memories are tortured. For the most part, Tom Hardy did the character the way he should be, and gave him the justice that he didn’t get under Schumacher’s direction in ’97. My one qualm with this Bane was his voice. The grumbling in The Dark Knight and the a-little-too-oldmanish way that Bane speaks leads me to believe that one of Christopher Nolan’s weaknesses is that he won’t always direct an actor’s voice when needed. This is a tiny weakness though, barely even chink in strong film making armor.

The writing in “DKR” is typically excellent and deep, as it is in every Nolan direction. The comic book version of Batman Begins’ Ra’s al Gul was immortal, not really an acceptable villain trait for this seemingly realistic incarnation of the Batman story. Screenwriters Christopher and Jonathan Nolan still managed to address the issue with literary mastery and with a nod to the source material. The storytelling is gripping and epic – not epic the way that any superhero movie is epic or even the way that “Begins” and “Dark Knight” were epic. “Rises’” predecessors tackled arguments about justice, good and evil, right and wrong, human imperfection, and common welfare and decency – things that Homer’s epics and even older ones tackled. There were long and life-changing journeys in the first two; hard questions were put forth to the hero. This time, we’re given a story that reads even more like an opera or a classic Greek poem. A city crumbles in every figurative and physical way. A government is destroyed and replaced. There is all-out war. It’s long and grueling, in a good way, and though there are intricate twists and turns, its conflict is “elemental,” as Nolan put it himself. The philosophical strokes are broader the third time, and that’s all right. We’re seeing good versus evil, freedom versus fear. It’s a conflict simple and strong. Bruce Wayne’s story is handled artfully. He’s searching for himself. Once his face was the mask and his cowl was the real person, but now that he’s retired the fugitive Batman, he has to find Bruce Wayne. It’s rough, considering his parents are dead and so is the love of his life. Bale has pulled off the greatest Bruce Wayne / Batman portrayal in history, simply and obviously because he’s the best actor who’s ever had the job (some voice coaching from Kevin Conroy wouldn’t be a bad idea.) Like The Dark Knight though, my biggest qualm with the film was how little about Batman and Wayne it actually was. The second film was called The Dark Knight, and was about the Joker, then Harvey Dent, then Bruce Wayne / Batman. This third film is again more about the villains than it is Bruce Wayne, and especially more about the villains than it is about Batman, and the ratio’s disparity is high. The biggest setback with this film was Wayne’s alter-ego, the Dark Knight. He had relatively little screen time and was disappointing in presentation. Batman Begins established that Batman would be working mostly at night, because criminals mostly work at night, and the criminal underworld, the narrows, was so densely built that sun couldn’t even shine in. It set Batman up to be the night crawler, the moonlight ninja, a vital aspect of Batman in every form of media since 1939. As it turns out, Batman operates in broad daylight now, in every scene except one (there’s another night scene but it lasts for about two minutes) and that one night scene isn’t all too iconic. Not once do we see him perched at the edge of a building in that classic gargoyle stance. Not once does he swing or rappel with the grapple gun. Not once does he glide with his famous cape. He doesn’t even seem to be concerned about concealment anymore. His ninja training in the power to make one’s self invisible is virtually unused. He walks through the front door of Bane’s lair when everyone is there and without doing any reconnaissance. He makes jokes to himself using the Batman voice when he’s alone. He walks around Gotham at high noon in a gray suit that looks more like something from the Halloween shop than the all-black apparel of Batman Begins, and his “new and improved” suit apparently can’t stop a knife like the one in “Begins” could. When dealing with the likes of the Joker and a bunch of subsequent villains who use knives and not guns, including in this film, keep the suit that’s shank proof. In Batman Begins, we didn’t actually see the Batman until an hour in, but once he arrived, he was the leader of some memorable scenes. The film was rife with the Bat soaring, swinging, and intimidating, less so in The Dark Knight, but at least it had some awesome Batman scenes including landing on Scarecrow’s car after freefalling down a spiral driveway, and the Hong Kong jump. It took quite a while for Batman to show up in this one, and once he did, we only saw him sporadically and he didn’t even do anything interesting. The fight scenes weren’t clever. Batman seemed to have forgotten his ninja training and just turned into a dumb brawler. How he threw the same plain punches throughout the whole movie, first getting beaten to a pulp, but later becoming a formidable match to Bane, is not explained, though I guess one could extrapolate psychological factors behind his pugilistic victory. The gadgets in his trusty utility belt basically go to waste as he only once seizes the opportunity to use them when they can be of great help. He also seems suddenly unable or unwilling to hide the fact that he’s Bruce Wayne anymore; what’s the point of a mask as an indestructible symbol if he lets just about everyone find out who’s under that mask? It was good to see Scarecrow again. Cillian Murphy craftily evolved the villain from a Hannibal Lecter type of creep to an escaped Arkham patient whose mind is just gone. Commissioner Gordon is again well played. Gary Oldman’s an accurate reflection of the comic book commissioner in look and lines. Joseph Gordon-Levitt has some show-stealing scenes as Officer Blake. Marion Cotillard plays Miranda Tate, a romantic possibility for Wayne, and an extremely well-crafted character. Concerning production values, everything was great as usual: tasteful and efficient cinematography, good editing and sound, great score (though I miss the small but noticeable James Newton Howard touch that the last two films had.) It’s the plot and story progression that turns me off. I understand that interesting villains and supporting characters are fun to sculpt and examine, but they shouldn’t make the main character seem like a supporter, especially if he’s Batman. Viewers might also be disappointed in a climax that’s quickly predictable and similar to another recent superhero movie.* I needed something, anything – just one scene where the Dark Knight looks like the silent guardian of Gotham after dusk, even if it was a final shot where he glides to camera (c’mon, that’d be a nice circle completion in relation to “Begins.”) I needed something iconic and memorable; that flaming Batsignal didn’t really satisfy. Expect two hours of compelling Selina Kyle, Bane, and Bruce Wayne material, as well as forty minutes of an uninteresting, un-sleuthing, dull, day-walking, flatfoot Batman. The mid-day sun rises. Now you can see why a parrot could be a passably good economist. Simply teach it to answer ‘supply and demand’ to every question!”

Such is the pleasant air of the cozy whodunit Murder at the Margin. This mystery is set in Caribbean St. John, where protagonist Henry Spearman’s vacation is interrupted by a homicide on the island. Spearman is a Chicago-school economist who’s at all times sighted by his profession.

Love, hate, benevolence, malevolence or any emotion which involves others can be subjected to economic analysis. When I say ‘I love you,’ it means my utility or happiness is intertwined with yours. Of course, the expression would be hard to work into a love song.”

The book was penned in 1978 by economists William L. Breit and Kenneth G. Elzinga under the pseudonym Marshall Jevons. On first printing there wasn’t any reference to the actual authors. In fact, the real authors put out a short farcical biography in which Marshall Jevons was described as sort of a sporting playboy millionaire (economics professors have fantasies too.) Readers of the right esoteric bent likely noticed the nom de plume was a hybrid of the names Alfred Marshall and William Stanley Jevons. Alfred and William were real-life 19th century economists. I’d be willing to bet that, before publication, Breit & Elzinga’s pen name had already spread throughout their field as a pleasant trivium.

In subsequent pressings Breit & Elzinga’s real names were revealed. After all, the glory & fortune of a niche mystery writer is one monumental step ahead of that of a prestigious economist (right!? - I howl to myself whilst pitching my own niche mystery.) More verifiably, Breit & Elzinga had intended for Murder at the Margin to be a teaching (especially self-teaching) tool anyway. The teaching purpose is well-executed. I was an economics major when I read Murder at the Margin. Integral to the splendid fiction are reinforcements of the basic economic tenets I’d learned in Micro and Macro 101 classes. After went through Stats easily enough but hit a wall at Calculus. No, my Econ Calc professor did not speak English, but I would have been toast either way. So I switched my major to some frivolity like English or Film. And here we are! Murder at the Margin really is intended for readers like me though. By “readers like me,” I mean economic lay people. I’d been told by several economics bachelors that an econ degree would help me understand all human behavior and therefore grow me wise to worldly mysteries. This novel charmingly reflects that outlook. Charming as it may be, it’s unsubtle and sometimes reads like YA textbook fiction with its stripped-down lessons. The thought struck Spearman that the proverbial visitor from Mars, if told that our world was divided into two kinds of economies, unplanned and centrally planned, would doubtless have thought the Cruz Bay dock represented remarkable planning. Every item seemed to be matched with someone who wanted it. And yet the neat meshing of wants with goods was brought about entirely through the operation of what Adam Smith had dubbed that ‘simple and obvious system of natural liberty.’ It was one of the paradoxes of economic theory and, Spearman believed, one of its greatest discoveries, that the most orderly economies were the least planned.”

Communists will hate this book.

Ahem, anyway – The theories presented might seem basic to any typical American reader who’s ever watched a presidential debate. But if while reading, one is already casually familiar with the elementary theories in Murder at the Margin, one might at least be further attuned to how much economics truly is a study of the world as a whole, beyond just finance. Economics is a synthesis of all human behavior, made up of tried principles galvanized by advanced mathematics (at least that’s what I hear the mathematics do.) It is the less-soft science behind anthropology, psychology, and political science. It also reflects the spectrum of mundane daily choices to deep religious beliefs. Spearman usually assumed individuals operated in their self-interest, not out of love. And while he attached no moral connotation to the self-interest assumption, he was troubled by Dyke’s assertion that people could be motivated solely by love. For many years an agnostic, he was reminded of a Bible verse from Hebrew school: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked.’ The verse struck a responsive chord, and he thought to himself that someday he would have to rethink certain theological issues.”

Professor Spearman assists – maybe pesters a little – the local police force in solving the latest town homicide through an economic mindset. The invisible hand, economists’ God-term for market forces, is keenly perceived by Spearman. This awareness is pivotal to the closing of the breezy 198-page mystery.

We’re also treated to the occasional nugget of truth from non-economist characters, which clarify Spearman’s assertion that his profession applies to everything. Oh, you see, Inspector, he married ‘up’ as they say, and people who do this can seldom feel at ease in their spouse’s circles.” “....it might be that a snobbish person realizes at bottom that his personality is not genuine, since his cues come from without and not from within.”

Purchase Murder at the Margin on Amazon.

Since hitting his creative stride in 2002 with Bloody Sunday, Paul Greengrass has been making two kinds of films. The first is the kind that is unsettling, conveys realism, exposes important socio-political factors, and entertains. These films are Green Zone, Captain Phillips, and the Bourne sequels. The second kind of film that Greengrass makes contains all of the same elements minus entertainment. They retell tragedies and sit their heavy circumstances and ramifications right in the pit of viewers’ stomachs. These films are Bloody Sunday, United 93, and Greengrass’ latest work, 22 July.

22 July relates the real-life events of the eponymous day in 2011 Norway. Then and there Anders Behring Breivik detonated a car bomb outside of an Oslo government building, killing 8, and proceeded to a teen campsite on the island of Utøya, where he killed 69 people. Greengrass’ entertaining action flicks have a self proclaimed “foot on the accelerator, full tilt adrenaline rush” from beginning to end.* But 22 July is part of that other family, not meant to be exhilarating. It’s portrayed as Bloody Sunday and United 93 are – slowly, the documentary-style tracking of characters providing a shaky omen. The omen ramps up to and immerses us in a tragedy. We don’t know what being there was really like, nor should we want to, but we are given a distant glimpse. Greengrass’ intention is to use such glimpses as a careful memorialization. He was successful at this, in my view. But I am part of the American audience that is his bread and butter. Norwegian reactions, based on the trailer’s YouTube comments, were more mixed than the U.S. reception. User Cheffy commented, “….making a movie and releasing it on NETFLIX thus showing it to the whole world gives Breivik exactly what he wanted." User Katharina Langsethagen commented, "Highlighting [Breivik] like this is wrong, and should not have been done in my opinion." User Smilende Blomst commented, "….making this movie sharing Breivik’s ideologi [sic] just helps him and his fucked up goal. Feels absolutely disrespectful. Also why make it in english [sic]?" These sentiments were in the top ten rated comments at the time of this article’s writing. They mostly seem to be posted by Norwegians. Many more replies throughout related similar dissatisfaction. A common Norwegian response was that the film gave too much attention to the perpetrator. Many comments disparaged 22 July in favor of Utøya 22. juli, a Norwegian-made film which apparently portrays the same event but does not portray the terrorist. (It had a very limited U.S. release and I haven’t been able to see it yet.) It seems like a lot of viewers from Norway contend that giving Breivik so much screen time, or even any screen time, is a distasteful glorification of the evil and harmful man. Greengrass received some similar flack for portraying the terrorist perspective in United 93 and the pirate perspective in Captain Phillips, but 22 July took on a markedly higher outcry for the same thing. I, an American, view all of Greengrass’ villain focuses as simply matter-of-fact-like, allowing considerations to be drawn from a realistic presentation. In the specific case of 22 July, I think the Breivik presentation only solidifies his guilt. His atrocities are accompanied by delusions of grandeur. These delusions, mainly that he is a beloved revolutionary, compound his evil and also appropriately belittle his twisted ideology (the ideology being, in short, that mass murder is the way to solve mass immigration.) The showing of Breivik also effectively contrasts and so helps sharpen how wronged the innocent victims were. Viljar Hanssen, played by Jonas Strand Gravli, is plagued with physical injuries, post-traumatic stress, and his impending testimony against Breivik. Hanssen is a singular microcosm of the Norwegian people – injured, shaken, supported, resolute. As shown though, perhaps this read of the film more reflects American sensibility than Norwegian. Norwegians, generally, seem to have a different taste for how real horrors are brought to film. But an important note on 22 July is that it is unabashedly made for U.S. (and other English-speaking countries) viewers. The characters speak English throughout even though it’s not the native or common language of Norway. It could be argued that only Norwegians should decide how to make art based on their tragedy, but I don’t think it’s a correct assertion. Unfortunately, there’ve been so many terror attacks in the world that I wasn’t immediately quite sure which one 22 July relayed. Almost all American moviegoers know and trust Paul Greengrass, and any project of his is sure to garner mass attention here in the States. Why do we need to have such a strong imprint of Norway’s July 22, 2011 in the United States? Many here can recall the French Le Monde's headline after the 9/11 attacks: "We Are All Americans." The line reflected a global solidarity with the injured and against terror. Watching 22 July I felt a similar bond and sympathy with the people of Norway. More immediately, 22 July illuminates the real, growing violence (and hypocrisy) of fascist groups. Neo-nazis are no longer just ostensibly harmless social Confederates. They exist all over the world, and their growth is currently the most dangerous and abhorent reaction to an admittedly real migrant crisis. Throughout his career, Greengrass has brought to film examinations, condemnations, and reflections of terrorism from a wide span of ideologies. The terrorist in his latest film is a white supremacist, an ilk which has unfortunately become a pertinent concern across the globe. Greengrass’s body of work continues to further confirm that no amount of innocent lives taken will ever rightly solve or ameliorate an issue. After seeing United 93 in 2006, I couldn’t bring myself to watch it again for over ten years. It was seemingly a very real portrayal of a real tragedy that most Americans my age or older are emotionally attached to. It and 22 July are not meant to be weekend reruns. A single viewing is enough to instill what matters most. With the horror of flight United 93 came a memorable response from the victims and their compatriots. An important part of it was the conveyance that terror will not be victorious. This was espoused as well by the people of Norway on 22 July, and IN 22 July. Paul Greengrass, once again, has done a caring and worthwhile job of crafting a cinematic memorial. 22 July is available to stream on Netflix. * https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQmdGGy1aVw Great Lines from "Pegasus Descending," a harrowing Southern crime novel by James Lee Burke9/25/2018

James Lee Burke is a master of the Southern novel, maybe the master of the modern Southern novel. I discovered him only a couple of years ago, just by walking through a store and coming across the alluringly titled Pegasus Descending. A name like that could cover a pretentious hipster epic, a cheesy political thriller, or as was this rare case, a brilliant drama.

I would have known how great Pegasus Descending would be if I had known basically anything about James Lee Burke. He has a Guggenheim Fellowship, two Edgar Awards, and a Grand Master Award by The Mystery Writers of America. The man writes detective mysteries that are critically received like Victor Hugo. Rightfully so. Some series novels must be read in order of release to best follow the plot and character development. This is also frequently not the case though. Instead of the overly expository world-building of an introductory installment, sequels often present their settings, style, and characters more naturally and with an easier pace. This notably applies to The Burning Land (The Saxon Stories) by Bernard Cornwell, and certainly to Pegasus Descending, which I didn’t initially know is the 15th of so-far 22 Dave Robicheaux novels. That’s not to say Pegasus Descending isn’t extremely descriptive. It is. While not hampering me down with too many details, Burke made characters and places as familiar as my own personal memories. ….he was a good kid, not a drunk, not mean-spirited or resentful yet about the addiction that had already cost him a fiancée and a two-bedroom stucco house on a canal in Fort Lauderdale. He grinned at his losses, his eyes wrinkling at the corners, as though a humorous acknowledgment of his problem made it less than it was."

Burke writes here from the perspective of Dave Robicheaux, an old Cajun Louisiana detective with a storied and tragic past. Part of that tragedy becomes integral to Pegasus Descending’s story when the daughter of a deceased friend comes to town and Robicheax starts connecting her appearance to the alleged suicide of a local girl.

In reality, Robicheaux’s musings might seem baroque for the average jaded old man. But he’s painted convincingly as a kind of warrior poet, who, from a long life of hard experiences, is just able to asses things with ornate accuracy. “ No, we don’t got a problem,” the short man said, turning toward me, the sole of one shoe grinding on a piece of broken mortar…. His eyes contained a cool green fire whose source a cautious man doesn’t probe." Then on a beautiful Friday night, with no catalyst at work, with a song in my heart, I put on a new sports jacket, my shined loafers, and a pair of pressed slacks, and joined the crew up in Opa-Locka and pretended once again I could drop lighted matches in a gas tank without consequence.” Later, I would remember the pro forma beginnings of the investigation like the tremolo you might experience through the structure of an airplane just before oil from an engine streaks across your window.”

Two of the experiences which vividly color’s Robicheaux’s life are the murder of his first wife and death of his second wife. From the little we read about them we can tell that they obviously torture him. As painful as those old losses are, his third wife, Molly, brings him a great new peace. He describes her appreciatively, with prose that could break a single philanderer’s ways.

Our little spot on East Main is a fine place to live, and the woman I share it with is a person who lays no claim on courage or devotion or resilience but possesses all those virtues in exceptional fashion without ever being conscious of them.” She used to be a catholic nun. She’ll rip your arms off and beat you to death with them."

In the quiet times, in the wee small hours when disjointed clues rattle in Robicheaux’s mind, it is Molly who appears to help him sort them out loud.

The official suicide ruling of a local good girl just doesn’t jive with Robicheaux’s keenness of human behavior. From his experience, the victim’s death and alleged life do not match.

Suicides fall into categories. Some victims probably manufacture an internal psychodrama as a way of asking for help, then drift too far across the line. The clinically depressed do it in closed garages or with pills and booze while they listen to Boléro or “Clair de lune.” Jumpers find audiences and sail out among the stars. Some fantasize a script in which they transcend their own deaths. In their imagination they watch from above while others find their bodies in horror and are trapped inside a legacy of guilt and grief for the rest of their lives.

Robicheaux calculates his case based on several other thought-provoking generalizations. Yes, they ignore exceptions and anomalies, but Robicheaux has a death to avenge, and to find the perpetrator he relies on his accumulated wisdom of how people, from their best to worst, commonly are.

But I knew that Raguza belonged to that group of human beings whose pathology is always predictable. By reason of either genetic defect, environmental conditioning, or a deliberate choice to join themselves at the hip with the forces of darkness, they incorporate into their lives a form of moral insanity that is neither curable nor subject to analysis. They enjoy inflicting pain, and view charity and forgiveness as signals of both weakness and opportunity. The only form of remediation they understand is force. The victim who believes otherwise condemns himself to the death of a thousand cuts There may be room in government service for the altruist and the iconoclast, but I have yet to see one who was not treated as an oddity at best and at worst an object of suspicion and fear.” But I believed that Whitey, like his mentors in Brooklyn and Miami, was driven by avarice, and like any man addicted to the love of money, his greatest and most abiding fear was not the loss of his life or even his soul.”

Robicheaux puts many characters in behavioral boxes, viewing them as people that reliably act one way and very likely can’t change except for the worse. An old cop speaking of people in general terms could perhaps cause a more sensitive reader to brace for racism. But Robicheaux is keenly aware of the horror of racial inequality, especially and specifically in his own home of the Cajun South.

New Iberia is not New Orleans and we do not share its violent history, one that in the past has included a homicide rate equaled only by that of Washington, D.C. Here, whites and people of color work and live side by side. But nonetheless a peculiar kind of racial ill ease still exists in our small city on the Bayou Teche. Maybe it’s indicative of the shadow that the pre-civil rights era still casts upon all the states of the old Confederacy. Perhaps we fear our own memories. I think as white people we know deep down inside ourselves the exact nature of the deeds we or our predecessors committed against people of color. I think we know that if our roles were reversed, if we had suffered the same degree of injury that was imposed upon the Negro race, we would not be particularly magnanimous when payback time rolled around. I think we know that in all probability we would cut the throats of the people who had made our lives miserable.

As we see in the excerpt above, he laments a violent dichotomy that The South has trouble shaking. He also notes subtler benefits that the well-off inherit.

I snipped the cuffs on each of his wrists and began walking him toward the backseat of my cruiser. Already his manner had changed and I realized he was exactly like all the middle-class kids we run for possession or DWI. Many of them are the children of physicians and attorneys and prominent businesspeople. When they deal with someone dressed in a suit, or in sports clothes, as I was, someone who represents a form of authority they associate with their parents, their vocabulary becomes sanitized and their manners miraculously reappear. In fact, their degree of humility and cooperation is so impressive, they usually skate on the charges or at worst receive probationary sentences.”

Along with, and sometimes integral to, the death and depression of Robicheaux’s environment are a few humorous passages.

Did you ever hear the story about Robert Mitchum getting out of Los Angeles City Prison?” I said.

Many of us have a friend who is always causing trouble, always needs help out of some jam, frustrates us, and occasionally makes us question how balanced our relationship is. There’s a lot of honor in the friendship just due to years, but maybe most importantly, the friend’s characteristics that frustrate us are the same ones that make us love the friend and provide near-death levels of laughter and camaraderie. If you’ve never known a person like that, you probably are such a person. Dave Robicheaux’s is Clete Purcel.

We’ve got a congressman here who was asked to describe Louisiana on CNN. He goes, ‘Half of it is underwater and half of it is under indictment.’” She looks over my shoulder and sees the security guys coming for us. Then she looks all around for her friends, but she’d already lost them in the crowd. She goes, ‘I’m up Shit’s Creek, handsome. Can you get us out of here?’ My big-boy started flipping around in my slacks, like it had gone on autopilot and was trying to break out of jail.”

Robicheaux has his own issues with a few different women. His carnal interests don’t get the better of him here though. He’s too consumed with the case, too grounded by his wife, and maybe too caught up with flowery analyses & descriptions? I’m not complaining.

She put a bright piece of red candy in her mouth and sucked on it. I looked her evenly in the eyes but did not answer her question, a bubble of anger rising in my chest like an old friend.” The guard was a stout, joyless woman who had once been taken hostage at a men’s prison and held for three days during an attempted jailbreak. I used to see her at Red’s Gym, pumping iron in a roomful of men who radiated testosterone – dour, painted with stink, possessed of memories she didn’t share. She unhooked Trish at the door. I rose when Trish entered the room and offered her a chair. The guard gave me a look that was both hostile and suspicious and locked the door behind her.”

“I was drunk for many years, Mrs. Lujan. But I finally learned everybody has to pay his tab.”

Robicheaux’s old vice turns into valuable experience for the Pegasus Descending case. It helps him better assess everyone and everything. He took a huge drag off his cigarette, his brow furrowing as though his inhalation of cancer-causing chemicals were a moment of metaphysical importance.” If you ever become a low-bottom boozer, you will learn that the safest places to drink, provided you know the rules, are blue-collar saloons, pool halls, hillbilly juke joints, and blind pigs where two thirds of the clientele have rap sheets.” The mist outside had become as thick and gray in the trees as fog, and I couldn’t see the green of the park on the far side of the bayou.

“What was it that bothered me so much? Loss of my youth? Fear of mortality? The systemic destruction of the Cajun world in which I had grown up?”

Robicheaux further reflects on these things quite a bit. His telling of the lost past and its destruction brings up a longing nostalgia in me for a place I’ve never been. Burke has composed a character that in one or many ways will reflect most readers' distinct emotions of unchangeable and irretrievable upbringings. It's sometimes verbose, always very good, writing. Traditional New Orleans was like a piece of South America that had been sawed loose from its moorings and blown by trade winds across the Caribbean, until it affixed itself to the southern rim of the United States. The streetcars, the palms along the neutral grounds, the shotgun cottages with ventilated shutters, the Katz and Betz drugstores whose neon lighting looked like purple and green smoke in the mist, the Irish and Italian dialectical influences that produced an accent mistaken for Brooklyn or the Bronx, the collective eccentricity that drew Tennessee Williams and William Faulkner and William Burroughs to its breast, all these things in one way or another were impaired or changed forever by the arrival of crack cocaine.” Its influence is systemic and I doubt if there is one kid in our parish who doesn’t know where he can buy it if he wants it…. At one time we literally set our watches by the Sunset Limited. It ran every day, from Los Angeles to Miami and back again, and somehow assured us that we were part of something much larger than ourselves–a country of southwestern vistas and cities glimmering at sunset on the edges of vast oceans, where the waves broke against the skin like a secular baptism. It was the stuff of mythos, but it was real because we believed it was real.” I have never given much credence to the notion that the dead are held captive by the weight of tombstones placed on their chests. I believe they slip loose from their fastenings of rotted satin and mold board and tree roots and the clay itself and visit us in nocturnal moments that we are allowed to dismiss as dreams. They’re in our midst, still hanging on for reasons of their own. Sometimes I think their visitation has less to do with their own motives than ours. I think sometimes it is we who need the dead rather than the other way around.”

As a homicide detective and widower and a generally nostalgic person, Robicheaux dwells at length on the dead. He ruminates pretty intently on everyone really (if you haven’t picked that up by now,) from well-intentioned people to evil ones, from the rich to the poor, young and old.

He was terrified of the prospect of hell and the consequences of his own libidinous nature, and believed it was the devil’s hand that constantly subverted his attempts to achieve social respectability, which in Bellerophon’s mind was the same as morality. For Bello, God was an abstraction, but the devil was real and reminded Bello of his presence each morning when Bello awoke throbbing and hard, chained to unrequited dreams that followed him into the day.” The Giacanos were stone cold killers and corrupt to the core, but they were pragmatists as well as family men and they realized no society remains functional if it doesn’t maintain the appearances of morality.” He wondered if the role of public fool came in incremental fashion with age, or if you simply crossed a line one day and found yourself in a room full of echoes that sounded almost like laughter.”

Robicheaux struggles against entering that room full of echoes as he ages:

Most cops and newspeople, usually at midpoint in their careers, come to a terrible realization about themselves, namely, that they are in danger of becoming like the jaundiced and embittered individuals they had always pitied as aberrations or anachronisms in their profession. But when people lie to you on a daily basis, when you watch zoning boards sell out whole neighborhoods to porn vendors and massage parlor owners, when you see the most expensive attorneys in the country labor on behalf of murderers and drug lords, when you investigate instances of child abuse so grievous your entire belief system is called into question, you have to reexamine your own life and perspective in ways we normally reserve for saints.

“You often rediscover your faith by taking up the cause of one individual….” For Dave Robicheaux, this one individual is Yvonne Darbonne. Drowning in a world and system and personal past that he can’t fix, he seeks solace in solving this one case, in bringing Yvonne’s killer to justice.

Get a great murder mystery and evocative Southern drama at the same time by reading Pegasus Descending. When people seek vengeance, they dig up every biblical platitude imaginable to rationalize their behavior, but their motivations are invariably selfish.”

Jurassic Park, Congo, The Andromeda Strain – Michael Crichton has penned several best-selling staples of the thriller genre. Most of them are sci-fi works primed for blockbuster adaptation.

Airframe (1996) is a similar horse but a very different color. Crichton really stripped down the fiction in science fiction this time. Contrary to most of his best known novels, there’s no emerging theoretical technology here. It all has to do with planes – no vanishing or supersonic or submersible aircraft, just planes as the commercial industry knew them at the time of publication. Even the plot itself is one of Crichton’s least fictionalized, composited from a few real-life incidents. In Airframe, Casey Singleton is a quality assurance VP for Norton Aircraft. One of their planes emergency lands at LAX with two dead and a few injured passengers. It’s Singleton’s job to find out why. The story has all the makings of a techno-thriller but is more of a techno-procedural, captivatingly meandering along through technical puzzles and diagnostics. When crafted by Michael Crichton, it’s these technicalities which actually do make for a good mystery. Crichton had made a name for himself by the time he wrote Airframe. That’s a good thing, because otherwise the subject matter wouldn’t grab many readers outside of those already interested in aviation. It’s surprisingly a page turner though. The dense science matter is an easy read, much like Andy Weir’s 2011 The Martian, and even more pivotal than that of Tom Clancy stories (great as they are.) Crichton illuminates a niche field, making it accessible to all readers, but the niche members may especially grin with familiarity at some of the industry stereotypes: She didn’t think Teddy was right about the airframe cracking; she didn’t think he was foolish enough to go up in a plane that hadn’t been thoroughly checked. He had hung around every minute of the tests, during the structural work, the CET, because he knew in a few days he was going to have to fly it. Teddy wasn’t stupid.

Neither the protagonist nor the story are primarily concerned with women’s progress, but I did find a certain compelling strength in how Singleton carries herself. It’s similar to Pam Landy’s in the Bourne film series. She is one of the best at what she does and makes her work invaluable to the right outcome in a field mostly populated by men.

Pilots, A&Ps, techno-thriller fiends, and general readers all will find Airframe a refreshing gem and hard to put down. It’s workmanlike, meticulously researched, and as is everything Michael Crichton, it’s a great read. They're engineers. Emotionally, they're all thirteen years old, stuck at the age just before boys stop playing with toys, because they’ve discovered girls. They’re all still playing with toys."

Many are familiar with Theodore Taylor’s The Cay, his 1969 masterpiece on racial tension and harmony between two island-stranded foils. It’s famous generally, and often required reading in American high schools.

Thematically, Taylor’s 1995 The Bomb is arguably similar to The Cay; both examine the stark and minute struggles between two vastly different cultures in an island setting. Both address the unfair advantages of the more privileged character(s.) Taylor’s presentation in The Bomb is quite contrary to The Cay’s though; The Cay has two characters, representing a general global relationship under a microscope. The Bomb has dozen’s of players, and explicitly portrays a prose version of a real-life international clash that directly changed the world. The more epic leanings of The Bomb prompted some to view it as less nuanced, and therefore worse, than Taylor’s better-known masterpiece. Some also argued that the real world events that shape The Bomb give him a pre-written narrative to follow, and an easier job of plotting. It certainly is less nuanced, but The Bomb is a gorgeous tragedy in it’s own right. The real world events do provide a skeleton for Theodore’s writing to follow, but it may very well have made his world-building more difficult than with The Cay. He had more meticulous research to conduct this time, which also brings a stressful chore of deciding how to make a good novel of said research and how far from it to veer. At the start, The Bomb recounts Japanese occupation of Bikini Atoll during WWII: In the world Sorry knew best, his family lived, worked, laughed, sang, and prayed as if war didn’t exist, as if the world stopped at the entrance to the lagoon. Suddenly they were captives, lazy natives, kin to monkeys. The Japanese didn’t need to say it. The message was in their eyes: You are inferior. You are worthless.

And so we are introduced to Sorry, a Bikini native who’s young, innocent perspective shapes the telling of Bikini’s evacuation by U.S. forces for nuclear tests after The Second World War.

Sorry said thoughtfully, 'Uncle Abram, why is it that the Americans want to test bombs when the war is over? Isn’t the outside world at peace now?'

The Bomb was somewhat disparaged for being preachy, and it is preachy, perhaps even a little oversimplified. But it’s appropriate, as our child-protagonist thinks in the simple moral terms that most children do.

As an American, extremely fortunate just to live in a prosperous and powerful nation, The Bomb gave me a stark, valuable reality-check. Our position in the world is often held not only from our own enterprise and the expense of our own troops, but also at the expense of many who’d originally had nothing to do with us. In the novel and reality, U.S. forces leave it up to the island leaders to vote on whether all the natives will vacate the island to a new home. The islanders are told that they’ll be able to return in a few years. This turns out to be untrue. Bikini natives and their families in 2018 are still unable to safely reside in Bikini Atoll again. Long-term nuclear explosion effects really weren’t fully known then. Taylor paints the likelihood though that the Americans knew more than they officially let on: Sorry and Tara talked for a few minutes with Dr. Garrison. Then Tara said, 'Please tell us the truth. When do you think we can come back here?'

“Tell no one. There must be hope.” This line struck me. It’s not an original sentiment but it’s worth heavy consideration every time it’s expressed. What is the worth of hope when statistically there is little or none? When, if ever, is it right to knowingly give people misplaced hope? [SPOILERS] This issue was recently and famously portrayed in The Dark Knight. Batman decides to take the blame for D.A. Harvey Dent’s atrocities, convinced that the respect of the well-known lawyer is more valuable to Gotham than that of the mythic Dark Knight. [SPOILERS END]

Soon the 1108 began to pull back, going in a half circle as the water deepened. Most of the villagers were lining the port rail on the top deck. Sorry looked around through a glaze of tears and saw that even the older men were fighting emotion. The hurt gripped chests and throats. Hands were held to lips.

Excerpts like the one above somberly reflect the bleak circumstances of the islanders as they vacate the only home they’ve ever known. Another passage miniaturizes what Taylor is doing to us as readers; he’s making things plain so that we better understand. Tara, a local teacher, has to do this after unsuccessfully explaining the specifics of nuclear bombs:

She saw that the class was lost already and put her hand to her forehead.

The Americans did have some arguable reasonable motives to consider. They’d just took part in defeating two tyrannical regimes that very well could have taken over the world if not for the partial help of the atomic bomb. The horrors of the last World War and the brinksmanship of the new Cold War necessitated that the U.S. excel technologically to maintain a safe global position. The bomb had to be tested somewhere. Right?

Somewhere, seemingly the middle of nowhere, can be someone’s entire life and world. Bikini Atoll was that for young Sorry. As in Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game, the fog of war is simultaneously thickened and cleared up a little through children’s eyes in The Bomb. Sorry had been to Lomlik dozens of times to pick coconuts, Jonjen many more times than that. Jonjen looked around their land. He said 'The white men always seem to spoil whatever they touch.' |